The “class wars” component of Netflix’s Culinary Class Wars is one of the most appealing aspects of the show. The South Korean series adds a dash of The Menu’s social-hierarchy tension and a sprinkle of Squid Game’s shifting alliance instability to its cooking competition format. Culinary Class Wars is about leveling the playing field and focusing on the elevation of the art of cooking at the forefront. It’s a blast because what Culinary Class Wars actually pulls off is the total shakeup of one of the most watched genres in my foodie family.

The competition opens by positioning 20 “White Spoons” (famous and prestigious chefs working in or affiliated with a vibrant South Korean food scene) against 80 “Black Spoons” (professionals on a smaller scale or from a lower-brow establishment, like a school lunch lady, the owner of a fried chicken restaurant, and a YouTube personality) in a battle for an astounding $200,000. Cha-ching to the winner. The White Spoons can be addressed by their real names as a sign of the respect they’ve earned over decades in the industry, but the Black Spoons can be called only by nicknames they’ve chosen for themselves, from Napoli Matfia (an Italian-cuisine specialist) and Goddess of Chinese Cuisine to Comic Book Chef (he specializes in dishes from graphic novels and comic books, which I found amusing).

As the series commences, the White Spoons are elevated onto a platform above the Black Spoons in a literalization of the “class” divide as an unseen, Wizard of Oz-like host explains that the Black Spoons are fighting for the same level of esteem. Only Black Spoons who get to the series’ final round of competition will stop being “nameless unknowns” and, as a sign of how far they’ve come, “shed their nickname and reveal their real name.”

The Black Spoons are often familiar with one another’s restaurants or reputations and greet one another excitedly as they arrive. But multiple White Spoons are mentors or onetime employers of Black Spoons and, by the second episode, cheer for them by name. Judge Anh Sung-jae initially doesn’t recognize or remember former employee One Two Three, a Black Spoon who spoke frankly in his talking-head interview about how intimidating it was to work for the chef as most reputed chefs do with a large number of employees.

In a counter to Chopped, the contestants’ tragic backstories are few. Culinary Class Wars incorporates blind tasting so famous chefs don’t get preferential treatment. Top Chef alumnus Edward Lee is competing as a contestant, but the assessments from extremely charismatic judges Anh and Paik Jong-won. The episodes’ pacing forces viewers to pay attention; instead of following a traditional three-act structure, climactic eliminations or judging decisions come 20 or 40 minutes in or even serve as cliffhangers before the series’ score blares over the closing credits.

Culinary Class Wars has no time for complacency, either from the competitors it pushes to the limits of their abilities or from us as viewers. Whenever it seems like the show has settled into a groove, it moves in a different direction—reorganizing the kitchen space, blowing up a team structure, or changing the parameters of the challenges, keeping things exciting.

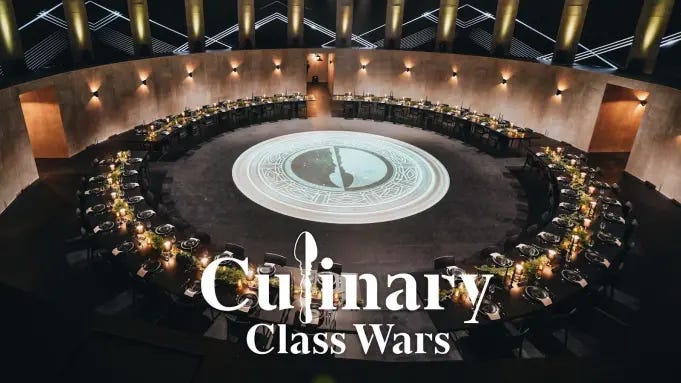

Like fellow South Korean competition series Physical:100, Culinary Class Wars’ greatest strengths lie in challenge engineering and production design, especially when they work in tandem. To whittle 80 Black Spoons down to 20, the competitors are shuffled into a giant room where they have to cook a signature dish at individual cooking stations while the White Spoons watch and comment from a perimeter balcony. Later, when the Black Spoons and White Spoons go head-to-head in dishes utilizing a specific ingredient, they wheel their meals into a room with rough-hewn walls where the blindfolded judges sit like fantasy creatures waiting to be coaxed out of their cave with special treats.

RELATED ARTICLE: Jinny’s Kitchen S2 Recipes : Lee Seo-Jin, Jung Yu-Mi, Park Seo-Joon, Choi Woo-Shik and Go Min-Si

There are surprises everywhere. Culinary Class Wars carves up its gigantic warehouse through hidden doors and secret rooms that reveal new pantries or guest judges who can overrule Anh and Paik about eliminations. The sordid departures of both Black and White Spoons who seemed like they’d go all the way are breathtakingly unsentimental; there’s no reliance on pleasant montage-style good-byes. To give us a little bit of transparency in contrast to the series’ other, more spontaneous decisions, the judges’ handwritten notes for dishes are blown up and shared onscreen, their immediate impressions on taste and technique providing us with more insight into competitors’ skills. Where other cooking shows feel codified in their structure and story arcs, Culinary Class Wars keeps adding little flourishes that poke holes in the distinction between fine dining and street food. A moment when Anh wonders whether he’s responding to a dish because of his own nostalgia and asks Paik to taste is a fascinating provocation, one that emphasizes the judges’ subjectivity and makes viewers question their own.

Drawing inspiration from the show’s finale, I cooked the beetroot pasta but made a small batch as it will cause indigestion if you consume too much. As a homemade pasta lover, I had to stop myself. I also cooked the Chinese-style stir fry in a wok, which was finger-licking good. I needed something to escape the pressure of my intense job-hunting application preparation cycle (digital and print media), and Culinary Class Wars is the show for me and for foodies alike. Wish me the best of luck as I try my best and send tailored applications everywhere, digitally and by post, wherever my skills can be utilized.

For the exact recipes of my tried and tested recipes, be sure to support; I will drop them shortly.